In 1998, an editor at Writers Digest asked me to contribute to an anthology about how to write fiction. I was then in my third decade as an author, and I wondered why I hadn’t thought of doing this earlier. After all, I devoted a lot of my life to education and have a Ph D in American literature. For sixteen years, I was a professor at the University of Iowa, teaching Hawthorne and Melville, Hemingway and Faulkner. It surprised me that I hadn't considered writing about writing.

In 1998, an editor at Writers Digest asked me to contribute to an anthology about how to write fiction. I was then in my third decade as an author, and I wondered why I hadn’t thought of doing this earlier. After all, I devoted a lot of my life to education and have a Ph D in American literature. For sixteen years, I was a professor at the University of Iowa, teaching Hawthorne and Melville, Hemingway and Faulkner. It surprised me that I hadn't considered writing about writing.

The result was The Successful Novelist: A Lifetime of Lessons about Writing and Publishing. I also began teaching workshops at writers’ conferences and at schools such as Columbia College in Chicago and Seton Hill University outside Pittsburgh.

At the top of this page, you'll find links to several of my essays about fiction writing, including "Five Rules for Writing Thrillers," "What’s In A Name?," and "Five Further Concepts." At the top, there's also a link to my essay, "Writing Comic Books," with emphasis on my Spider-Man: Frost two-parter.

If you'd like to read a sample chapter from The Successful Novelist, click here.

Watch a 90-second video of my writing advice. Click here.

I recorded a 90-minute video webinar that offers an abundance of advice about writing and publishing. It's called The Writer's Toolkit, and it's available, with extras, from Wordharvest. Click this link for more information.

Thrillers have never been more popular. On the New York Times fiction bestseller lists, over half are often filled with examples of the genre. Thrillers even have their own organization, International Thriller Writers (which I co-founded with Gayle Lynds). But thrillers didn’t always have this presence. Back in 1972, when my debut novel, First Blood, introduced the character of Rambo, bestseller lists favored a mix of literary, sentimental, and historical fiction as well as the sort of celebrity gossip novels that we identify with Harold Robbins and Jacqueline Susann.

Not that thrillers were entirely absent. Michael Crichton’s The Terminal Man appeared on the New York Times list that year, but it was considered an exception. Only in the twenty-first century did thrillers become so unusually dominant. The reasons for that are complicated and a subject for another essay. (See Steve Berry’s concluding essay in Thrillers: 100 Must Reads for an insightful discussion of this topic.)

If you’re a writer who’s thinking of going in this direction, here are five pieces of advice that might help.

NUMBER ONE: KNOW YOUR MOTIVES

Have a good reason for writing a thriller. Some personal background will illustrate my point. After my father died in World War II, severe financial problems forced my mother to put me in an orphanage. She later remarried and reclaimed me. My stepfather hated children. The arguments in my home were so verbally violent that I put pillows under my covers to make it seem that I slept there when I was actually cowering under my bed.

I remained sane by imagining stories in which I was a hero overcoming adversity. I escaped into books that were like the Alfred Hitchcock films I snuck into theaters to watch. When I became an adult, is it any wonder that the stories I felt compelled to write are thrillers? Every word of them carries the conviction of the stories that distracted me in my troubled youth.

By contrast, if you’re merely writing thrillers because they’re currently popular, you ought to think twice. Few activities wear a writer down more than laboring on a book that isn’t personally meaningful. After a while, writing that book becomes the equivalent of carrying a heavy extension ladder.

What’s more, events might prevent the book from being published. On September 11, 2001, when terrorists rammed those passenger jets into the Pentagon and the World Trade Center buildings, the message went out from publishers, “Don’t send us thrillers. People will no longer want plots that have bombs and guns and death. The days of violence in books are over. Society is experiencing a permanent change toward the need for peace and gentleness.” That lasted six months. During those months, editors routinely rejected thriller manuscripts, believing that thrillers were out of touch with what readers wanted.

Imagine how hollow you would have felt if you’d written one of those thrillers just to pay the bills. The only valid reason to write a thriller or any other kind of book is that you’re absolutely driven to create it. The idea nags at you until you can’t resist immersing yourself in that universe. If the book doesn’t sell, at least you gained the personal satisfaction of bringing it into the world. But if you didn’t care about it in the first place, you sadly wasted your time.

Before I start any novel, I write a lengthy answer to the following question: “Why is this project worth a year of my life?” If I’m going to spend hundreds of days alone in a room, I’d better have a good reason for writing a particular book.

NUMBER TWO: KNOW THE GENRE’S HISTORY

Each year, I teach at many writers’ conferences. I’ve lost count of how many authors came to me with ideas that they thought were original but that had already been around the block several times. For some of these writers, the history of the thriller genre begins with Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. For others, it begins with Tom Clancy’s military-hardware novels or Thomas Harris’s serial-killer novels or John le Carré’s realistic espionage novels.

In contrast, a knowledgeable author might have said that the genre dates back a century and a half to 1860 when Wilkie Collins published The Woman in White and reviewers believed that Collins had created something new: the novel of sensation. But the fact is, thrillers date back hundreds and thousands of years, all the way to the origin of story telling. We can’t recognize when a plot is hackneyed if we don’t educate ourselves about the best that has been done in the genre.

To provide examples, I co-edited (with Hank Wagner) an International Thriller Writers project, Thrillers: 100 Must Reads, in which 100 contemporary thriller writers each provide a 1,000-word appreciation of a thriller with historical significance. We need to be experts in the history of the type of story we write, but our obligation doesn’t end there. In the introduction to Thrillers: 100 Must Reads, I comment on the numerous different categories within the genre: the legal thriller, the medical thriller, the political thriller, the spy thriller, the high-action thriller, etc. If you’re writing a particular kind of thriller, become an expert in that category until you could give a lecture about it. Imagine the embarrassment of proposing a plot idea to an editor, only to be told that it’s been done to death.

NUMBER THREE: DO YOUR RESEARCH

You don’t need to be a physician or an attorney to write a medical thriller or a legal thriller, but it sure helps if you’ve been inside an emergency ward or a courtroom. Read non-fiction books about your topic. Interview experts. If characters shoot guns in your novel, it’s essential to fire one and realize how loud a shot can be. Plus, the smell of burned gunpowder lingers on your hands. Don’t rely on movies and television dramas for your research. Details in them are notoriously unreliable. For example, the fuel tanks of vehicles do not explode if they are shot. Nor do tires blow apart if shot with a pistol. But you frequently see this happen in films.

I love doing research. It makes me a fuller person. For The Shimmer, whose main character is a private pilot, I took flying lessons and earned my pilot’s license. For Double Image, a novel about a war photographer, I attended a three-month photography class, interviewed professional photographers, and spent many Saturdays in photography galleries. For The Fifth Profession, The Protector, and The Naked Edge, I received intensive training from protective agents. For The Spy Who Came for Christmas, which takes place during a Christmas Eve snowfall on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road, one of the ten most distinctive streets in the United States, I walked that street on a snowy Christmas Eve to verify the details of that famous location. For outdoor survival sequences in Testament, I spent five weeks with the National Outdoor Leadership School in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming.

The point isn’t to overload your book with tedious facts. Rather, your objective is to avoid mistakes that distract readers from your story. If you’ve done your research, readers will sense the truth of your story’s background. In addition, the topic should interest you so much that the research is a joy, not a burden.

NUMBER FOUR: BE YOURSELF

Be a first-rate version of yourself rather than a second-rate version of another author. Innovate rather than imitate. The key to being a successful thriller novelist involves establishing an identity.

My friend, Joseph Finder, offers a good example. A spy novelist, in 2004 he looked for a new way to write about espionage. He paid attention when a business executive happened to mention that espionage wasn’t only a major factor in politics and the military but that it was also rampant in corporations. Joe investigated the subject, wrote Paranoia, and introduced the corporate espionage novel. Similarly, Lee Child’s Jack Reacher books introduced something new by revitalizing the archetype of the wandering western gunfighter and putting it in a modern context.

Our task is to move the genre a step forward so that other thriller writers must absorb what we’ve done if they themselves want to move the genre forward.

NUMBER FIVE: AVOID THE GENRE TRAP

When you finally start writing, forget that your book is a thriller. All fiction fits into one kind of genre or another, even so-called literary novels. Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections is a dysfunctional-family novel, for example. I read many types of books, and all I care about is the quality of the writing, the appeal of the story, and the power of the characters. Some authors believe that because they’re writing thrillers, they don’t need to apply standards. That can only lead to inferior work. We should want to write the truest, most exciting, most moving and meaningful novel that we possibly can. The great thrillers do that, which makes them literature.

(This essay originally appeared in Romantic Times magazine, December, 2008. It was reprinted in Many Genres/One Craft: Lessons in Writing Popular Fiction ed. by Michael A. Arnzen and Heidi Ruby Miller, Headline books, Inc., 2011. Both Michael and Heidi are affiliated with Seton Hill University, one of the few American institutions of higher learning to offer an MFA in genre writing. I was a guest lecturer at Seton Hill’s excellent program several times and highly recommend both it and Many Genres/One Craft. You’ll find other suggestions about writing in my book, The Successful Novelist.)

A rose by any other name would smell as sweet. Nonetheless many authors have an almost mystical attachment to the names they give characters. I once had a discussion with a fellow author who heatedly insisted that “Decker” was better than “Becker.” The artist hero of my novel Burnt Sienna was originally called Kincaid, but my editor got nervous because there was a real-life artist with that name (although spelled differently), so in anguish I changed Kincaid to Malone. For about a week, I felt intense loss. Now I have trouble recalling the original name.

Names can have thematic significance, yes. The aging cavalry scout in my historical western Last Reveille is called Miles Calendar, words that suggest both distance and time. Also miles is Latin for “soldier.” But if we ignore a name’s meaning and think of it as an abstraction, we can avoid a lot of problems.

At the midst of a project, I find it useful to list the names of all my characters to ensure that each begins with a different letter of the alphabet, thus preventing a repetition of Anna, Albert, and Arnold. The list also helps me avoid a lot of names with similar endings: Harry, Bobby, and Audrey. In both cases, the names are sufficiently similar that readers will have trouble distinguishing the characters.

Note that the names Harry, Bobby, and Audrey also have the same syllables, as do Corrigan, Matheson, and Farraday, names that would be rhythmically wearying if all three were main characters in the same story, not to mention that Corrigan and Matheson both end with “n”.

Prepare a chart for names of one, two, and three syllables. Make sure there’s plenty of variety and that the names don’t begin and conclude with the same letters to avoid causing a blur. While all this might sound obvious, if you list the names in your current project, you might be surprised by the unfortunate patterns you discover.

Because of audio books, I also try to avoid names with “s” in them. “Susan said” challenges even the best actor. (Say that sentence out loud.) For me, the goal is to choose names that don’t inadvertently draw attention to themselves and distract the reader from the story.

(This writing tip from David first appeared in Sherrilyn Kenyon’s Character Naming Sourcebook, Writer’s Digest Books, 2005. You’ll find many similar helpful strategies in David’s writing book, The Successful Novelist.)

NUMBER ONE: FLOW

A story is a living thing. Our goal should be to serve it and do what it wants, to be its instrument. Its flow from our imagination to the page is impeded in two main ways—if we try to make the story do something that it doesn’t want to do, or if something in us isn’t ready to face the full implications of the story’s theme and emotions. Avoiding those blocks requires developing a relationship with the story, as if it were a person. At the start of each writing session, especially if I’m having trouble moving a scene forward, I literally ask the story, “What do you want to do? Where do you want me to go with you? Why are you stalling?” This is a psychological trick that almost always creates an imagined response, along the lines of “This scene is boring. Why are you making me do it?” or “This scene is full of gimmicks. Why aren’t you being honest with me?” The device takes only a minute. It’s part of my ritual, and over the years, it saved me from writing a lot of scenes that were either unnecessary or else dishonest.

NUMBER TWO: INSPIRATION

In my writing classes, I devote a session to daydreams, which are spontaneous messages from our subconscious. After one of my presentations, a puzzled member of the audience raised his hand and asked what a daydream was. Others were surprised, but I wasn’t. Not everyone has a daydream-friendly mind. In fact, some people have been taught to repress daydreams as a distraction and a waste of time. Fiction writers, however, tend to have plenty of daydreams, and they should not only welcome those daydreams but train themselves to be aware of them. Daydreams are our primal storyteller at work, sending us scenes and topics that our imagination (i.e. our subconscious) wants us to investigate. Each day, we should devote time (I usually do this before sleeping) to reviewing our daydreams and determining which of them insists on being turned into a story. The more shocking the daydream, the more truthful about us it is, but often we push away those daydreams that make us uncomfortable when we should actually embrace them. The core of most of my novels came from daydreams.

NUMBER THREE: CLARITY

The great film director, Billy Wilder, was once asked if he liked subtlety in a story. He answered, “Yes. Subtlety is good—as long as it’s obvious.” The same thing can be said about complexity and simplicity. Some stories are so complex that it’s frustratingly impossible to understand them. But other stories (like Wuthering Heights or Bleak House) are complex in a way that we don’t find difficult to understand and that we actually find enjoyable because of the complexity. Conversely, Hemingway’s famous simple style is in fact very complex. What really matters is whether something is clear. Each day, as I revise the pages from my prior writing session, I take a few minutes to ask myself, “Is this clear? Will the reader understand it?” Don’t be afraid to deal with a complex topic in a complex way, using multiple viewpoints and the like, but always keep in mind that clarity will make you the reader’s friend.

NUMBER FOUR: PACE

William Goldman’s Adventures in the Screen Trade is about screenwriting, but much of that wonderful book can also be applied to fiction. Goldman says that in his screenplays he tries to get into each scene as late as possible and to get out of the scene as early as possible. Faulty pace in a novel can be corrected, using his advice. Unless you’re writing an imitation of a nineteenth-century novel, there isn’t any need to begin scenes with the laborious process of introducing those scenes and explaining how characters arrived there. (“He woke up that morning, drank two cups of coffee to subdue his hangover, and took a taxi to his lawyer’s, arriving a half-hour late.”) This is dull telling. Chances are that the interesting part of this scene begins just after the introduction. Similarly, many writers tend to put an empty paragraph at the end of a scene. When revising, I take a minute to experiment by cutting the first and last paragraph of each scene. Suddenly, a sequence that dragged can become speedy. Arrive late in a scene and leave early. The reader will fill the gaps.

NUMBER FIVE: EVOKING EMOTION

Hemingway spoke about a story’s “sequence of motion and fact.” James M. Cain discussed “the algebra of storytelling: a + b + c+ d= x.” What they meant was a sequence of incidents in a story that, if arranged correctly and dramatized vividly, will create a stimulus that compels the reader to feel whatever emotion the author is trying to create. Talking about emotions won’t compel a reader to feel those emotions. “He felt sad” won ‘t make a reader feel sad. Instead, the reader must be made to feel the situations in the story, to experience what the characters experience, and as a result, just as a sequence creates emotion in the characters, it will also do the same in the reader. This is a case of stimulus-response. Writers can achieve this effect if they take the sense of sight for granted and emphasize the other senses, thus creating scenes that are multi-dimensional. (Details of sight almost always create a flat effect.) When revising, I always take a minute to make sure that each scene has at least two sense details besides those based on sight. In this way, the reader becomes immersed in the story, feeling it rather than being told about it.

(These writing tips from David originally appeared as “Five Ways To Improve Your Writing in Thirty Minutes a Day” in Writer’s Digest, February, 2011. You’ll find many similar helpful strategies in David’s writing book, The Successful Novelist.)

“Aunt May, did you know most spiders build a new web every morning? By noon, they sometimes need to repair the web or build another one completely. They do that every day, again and again. All their lives. Maybe as winter comes, those spiders don’t die because they’re cold but because they’re worn out.”—Peter Parker

“Aunt May, did you know most spiders build a new web every morning? By noon, they sometimes need to repair the web or build another one completely. They do that every day, again and again. All their lives. Maybe as winter comes, those spiders don’t die because they’re cold but because they’re worn out.”—Peter Parker

“Don’t talk about dying.”—Aunt May

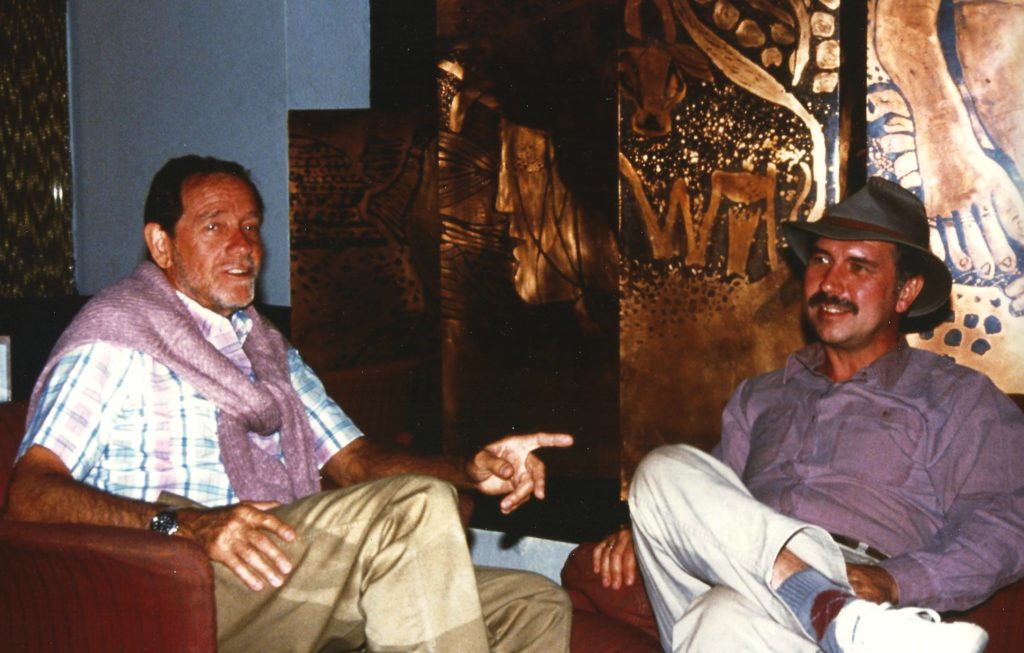

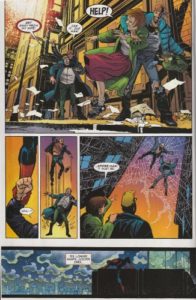

After my six-part Captain America: The Chosen comic-book series was published, Marvel Comics asked me to write a two-part series about another of their iconic superheroes: Spider-Man. Because comics are a visual medium, I looked for a way to highlight Spider-Man’s colorful costume. For Captain America: The Chosen, I had used Afghanistan’s bleak mountainous landscape to emphasize Cap’s brilliant red-white-and-blue appearance. For Spider-Man, I decided to use the contrast of snow.

What if a “storm of the century” blizzard struck New York City? Although I considered having a malevolent spirit at the heart of the storm, I finally preferred to make the storm realistic. One exaggeration is sufficient in a comic book. The reader is willing to grant that Peter Parker can turn into a superhero. But after that, how many other “super” ingredients can a story sustain? A force of nature can be as frightening as an evil spirit, I decided, and although several supervillains do appear in this story, they remain within the bounds of realism because they’re hallucinations as Spider-Man collapses in a snowdrift.

I decided to make other aspects of the story realistic also. The scene in which Peter Parker keeps shivering as he stands under a steaming shower illustrates this approach, especially the close-up of his Spider-Man costume lying in a grimy heap on the shower stall’s floor. Who would have thought that superheroes showered or that their costumes needed laundering? In later scenes, artist Klaus Janson emphasizes Peter Parker’s whisker shadow after his torturous night. And who’d have thought that superheroes needed to shave, or that a couple of pages could be devoted to the kind of life/death/spider-web dialogue that I quoted at the start of this essay?

With great power comes great responsibility. That phrase has been associated with Spider-Man since the first comic book that featured him. Determined to go to the core of what it means to be Peter Parker and Spider-Man, I constructed FROST so that it explored the personal meaning of great power and great responsibility. The crux of the story became this: Aunt May is freezing to death. Spider-Man sets out to save her. But during his frantic mission, he keeps finding people who also desperately need his help. One scene that emphasizes Spider-Man’s anguish involves a pregnant woman trapped in an ambulance. She and her baby will die if Spider-Man doesn’t save her. But maybe Aunt May dies while he chooses to help someone else. Who is more important: a young woman in childbirth or an elderly woman who happens to be Peter Parker’s aunt? As Spider-Man says near the end of the story, “So many people were in trouble. Sometimes it’s impossible to know the right choice.”

A friend once glanced at some pages in my Captain America: The Chosen series and told me, “Well, you didn’t need to do much writing.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, there’s hardly any dialogue.”

Almost laughing, I explained that a script for a comic book is more complex and detailed than he realized. The writer suggests the number of panels per page, describes what happens in each panel, and adds dialogue captions. The artist then interprets these pages, adding or subtracting panels and emphasizing items that appeal to the artist’s imagination. Because the illustrations are usually in black and white, a colorist completes the process.

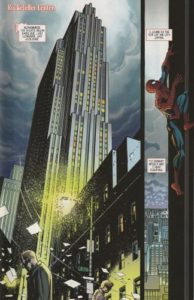

Here are pages from my script for Spider-Man: Frost before they were given to legendary Klaus Janson (Batman: The Dark Knight, Daredevil, etc.) and colorist Steve Buccellatto. The latter added an impressive brilliance to the blizzard scenes.

Apart from the considerable amount of description, the first thing you’ll notice is that while I suggested three panels for page 1, Klaus decided to use only two. Sometimes Klaus extended the number of panels per page while at other times he retained the arrangement of panels as I described them. To accommodate any changes Klaus made, I often needed to rewrite captions or provide new ones.

This is what the script for pages 1 and 2 looks like. Comparing them with the finished result shows how much this is a collaborative process. (Note that panel descriptions are put in bold type whereas dialogue is in plain type. These are formatting conventions.)

Page 1

PANEL A: Night. Brown leaves and a newspaper blow along a city street. If we look closely at the newspaper, we see the letters  GLE, as if this is the front page of THE DAILY BUGLE. From pavement level, we peer up toward a chilled-looking man who walks past, resisting the wind by holding a hat to his head and pressing his overcoat to his chest. His breath comes out as frost, blown by the wind. But what we really care about is the magnificent skyscraper that towers above him, its crest disappearing into the dark sky. This panel occupies the entire left side of the page.

GLE, as if this is the front page of THE DAILY BUGLE. From pavement level, we peer up toward a chilled-looking man who walks past, resisting the wind by holding a hat to his head and pressing his overcoat to his chest. His breath comes out as frost, blown by the wind. But what we really care about is the magnificent skyscraper that towers above him, its crest disappearing into the dark sky. This panel occupies the entire left side of the page.

SPIDER-MAN: November. The nights begin earlier . . . last longer . . . get colder.

PANEL B: We’re on a platform at the top of the building. Beyond it, the glittery view of Manhattan emphasizes the Empire State Building. Dark clouds churn above the city.

SPIDER-MAN: Rockefeller Center.

PANEL C: Spider-Man slumps against a glass barrier. This new angle favors the Statue of Liberty in the distance. He looks exhausted. His costume is grimy. One shoulder is torn. His breath, too, comes out as frost, blown by the wind.

SPIDER-MAN: I come here often . . . to remind myself of what I fight for.

Page 2

PANEL A : Night. Another newspaper page blows past. Outside a corner grocery store, a gang member yanks a purse from an old woman bundled in a threadbare coat. A second gang member draws back a hand to punch an elderly man who tries to intervene. A bag of groceries lies on the sidewalk, milk leaking from a broken carton.

old woman bundled in a threadbare coat. A second gang member draws back a hand to punch an elderly man who tries to intervene. A bag of groceries lies on the sidewalk, milk leaking from a broken carton.

ELDERLY MAN (FROST FROM HIS MOUTH): Get away from my wife!

PANEL B: The second gang member looks startled when a red-gloved hand streaks down from above and grabs his fist.

PANEL C: The first gang member gapes as his buddy is yanked upward.

PANEL D: The elderly man and woman gaze up in amazement as the two thugs dangle from a gigantic spider web.

PANEL E: The observation deck. A different angle of Spider-Man slumping against the glass barrier. The glow of the city behind him is now muted by the clouds.

SPIDER-MAN: Yes, longer nights . . . colder ones . . .

Page 1 is different from what I wrote, and yet it communicates the same idea while giving Klaus a chance to follow his inspiration. The script and artwork for page 2 are nearly identical, except that I later added captions to panels B and D, feeling that they needed something extra.

Here’s one of the most intricate layouts in the entire sixty pages. The arrangement of images is so unusual that expressing them in words was a challenge. Klaus’s images and Steve’s colors are eye-popping.

Page 24

PANEL A (ALL THE WAY ACROSS THE TOP OF THIS PAGE AND THE NEXT): Amid streaking snow, massive poles support power lines that stretch across a section of countryside. Tall, snow-laden fir trees stand next to the power lines.

Along the bottom:

PANEL B: Angle on one of the fir trees. Its branches are weighed down by heavy snow.

PANEL C: Close view on one of the branches, bent low by the weight of the snow.

PANEL D: The top third of the fir tree breaks off.

SFX: CRAAAACCCCCKKKK

Page 25

Continuing along the bottom of the page.

PANEL A: The falling tree hits the electrical lines, causing wires to snap.

PANEL B: Sparks fly as the snapped wires are blown by the snow.

PANEL C: The Manhattan skyline. We see the storm-obscured lights of the city.

PANEL D: The same view of the skyline, but now all the lights are off.

In some ways, a comic book is like a storyboard for a film. The gap between panels, the jump from image to image—these create the illusion of movement through stop-action storytelling. What’s left out is often as important as what we see.

The medium is also a book. I think of each page as the equivalent of a paragraph. In addition, the most powerful images can be positioned so that they can’t be seen until a page is turned and the reader is surprised by what the new page reveals. In this way, the act of reading a physical comic book becomes part of the drama of the story.

If you’re not familiar with the comic-book world, perhaps these few comments will help you appreciate the detailed preparation that goes into this complicated form of storytelling.

David Morrell

Copyright © 2013 by Marvel Comics and David Morrell. Included in The Amazing Spider-Man: Peter Parker, The One And Only, a collection that includes “Spider-Man: Frost.” All rights reserved. (For a complete list of David’s Marvel comic books, please go to the BOOKS page of www.davidmorrell.net.)

Over the years, I’ve given perhaps a hundred talks about writing at various conferences. Only one was ever video recorded—at the Southwest Writers monthly meeting in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in March, 2020. This is a rarity. To view my presentation, play below or click here.