Rambo

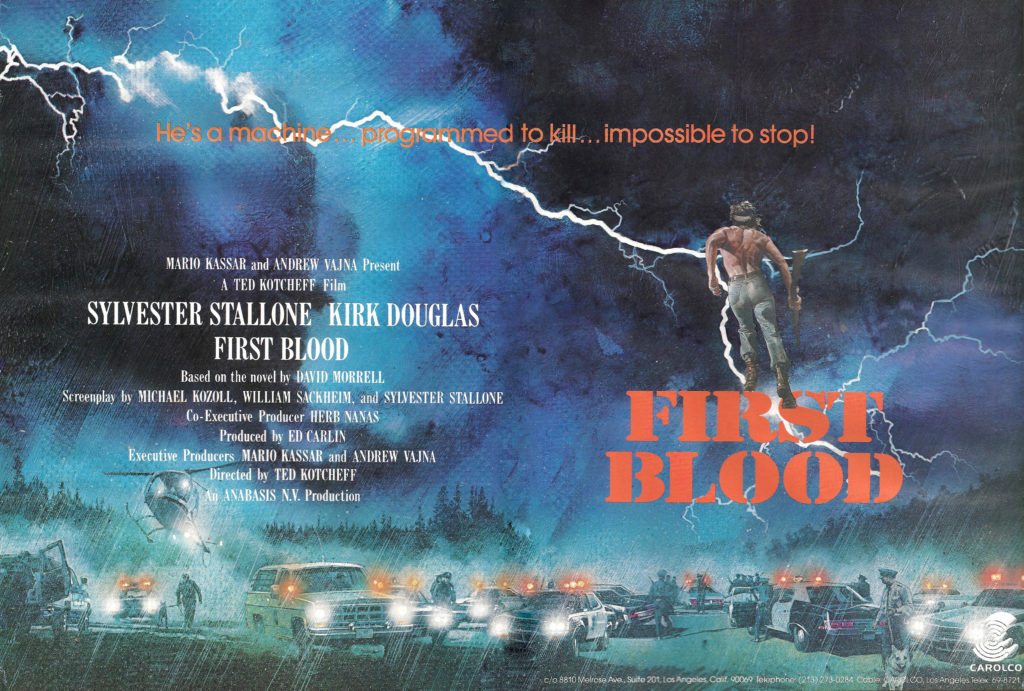

In 1972, I published my debut novel, First Blood. Called “the father of the modern action novel,” it was widely and enthusiastically reviewed. It was taught in high schools and colleges. It became a 1982 film, starring Sylvester Stallone, and led to a series of films about Rambo, who joined the ranks of the top five internationally recognized thriller icons: Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, James Bond, and Harry Potter.

In 1972, I published my debut novel, First Blood. Called “the father of the modern action novel,” it was widely and enthusiastically reviewed. It was taught in high schools and colleges. It became a 1982 film, starring Sylvester Stallone, and led to a series of films about Rambo, who joined the ranks of the top five internationally recognized thriller icons: Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, James Bond, and Harry Potter.

Eventually, I wrote novelizations for Rambo (First Blood Part II) and Rambo III. I also wrote an in-depth essay, Rambo and Me: The Story behind the Story. In addition, I contributed a full-length audio commentary to home-video discs of First Blood, discussing my novel and the film.

Gauntlet Press published signed, numbered collectors' editions of all three Rambo novels, with an abundance of extras, including informative essays that are essential to an understanding of the background to the series. There are unpublished chapters, script pages, photographs, publicity posters, and a ton of other items. These definitive versions are available only from Gauntlet Press and a few other on-line sources: 500 copies of the numbered version and 52 copies of the lettered version. Here's a link to Gauntlet Press and more information. These special editions are now out of print but might be available at secondary markets, such as eBay and ABE books.

Gauntlet Press published signed, numbered collectors' editions of all three Rambo novels, with an abundance of extras, including informative essays that are essential to an understanding of the background to the series. There are unpublished chapters, script pages, photographs, publicity posters, and a ton of other items. These definitive versions are available only from Gauntlet Press and a few other on-line sources: 500 copies of the numbered version and 52 copies of the lettered version. Here's a link to Gauntlet Press and more information. These special editions are now out of print but might be available at secondary markets, such as eBay and ABE books.

Let’s start with some basics. First Blood was your first novel, right?

Yes, it came out in 1972. Debut novels almost always sink, but I was fortunate. Just about every major newspaper and magazine gave it glowing reviews. A film studio bought the movie rights before it was published. It was translated into 26 languages. It was taught in high schools and colleges. When Stephen King taught creative writing at the University of Maine, it was one of the two texts he used. (The other was James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity.) Even after forty-five years, it has never been out of print.

The book introduced Rambo, who turned out to be one of the five most iconic thriller characters of the twentieth century, along with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, James Bond, and Harry Potter. How does it feel to have created a character recognized around the world?

Rambo is mentioned almost daily in conversation or in the media. The word is in the Oxford English Dictionary. Astro-physicists use the word Rambo to refer to a powerful group of dead stars. He’s so much a part of world culture that when I sign copies of First Blood, I often call myself “Rambo’s father.” It’s like he’s a son who grew up and went in unexpected directions. There’s no way to predict the future of a character or a book. I tried to write the best novel I could. After that, it was out of my control. When I hear Rambo mentioned, I’m often caught by surprise and take a second to remember that I created him.

How did you get the idea for the story?

I was raised in southern Ontario. In the mid 1960s, I came to the United States to study American literature at Penn State. At that time, Vietnam was hardly mentioned in Canada, so I had no idea what the war was about when I met students recently returned from Vietnam. I learned about their problems adjusting to civilian life: nightmares, insomnia, depression, difficulty in relationships, what’s now called post-traumatic stress disorder. In 1968, the two main stories on the television news were Vietnam and the hundreds of riots that broke out in American cities after the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy. I got to thinking that the images of the war and the images of the riots weren’t much different. Eventually I decided to write a novel about a returning Vietnam veteran who brings the war to the United States. That’s the short answer.

And what's the long answer?

Rambo is a complicated subject with all kinds of twists and turns. I have a long essay, Rambo and Me: The Story behind the Story, that's available as  one of my e-works and that's included in the Gauntlet Press collector's edition of Rambo (First Blood Part II). In it, I talk about all the things that were going on in the late 1960s that made me want to write the novel, particularly the riots and the student demonstrations against the Vietnam War. In my introduction to First Blood and in my writing book, The Successful Novelist, I discuss how the key to the novel was the way scenes alternate between Rambo’s and Teasle’s viewpoints so that the reader doesn’t know who to cheer for. They represent the two sides of American culture as I saw it in the late 1960s.

one of my e-works and that's included in the Gauntlet Press collector's edition of Rambo (First Blood Part II). In it, I talk about all the things that were going on in the late 1960s that made me want to write the novel, particularly the riots and the student demonstrations against the Vietnam War. In my introduction to First Blood and in my writing book, The Successful Novelist, I discuss how the key to the novel was the way scenes alternate between Rambo’s and Teasle’s viewpoints so that the reader doesn’t know who to cheer for. They represent the two sides of American culture as I saw it in the late 1960s.

That device wasn't used in the movie.

No. In the film, the police chief gets less screen time than Rambo while in the novel he and Rambo are equal.

So, does that mean you don't like the film?

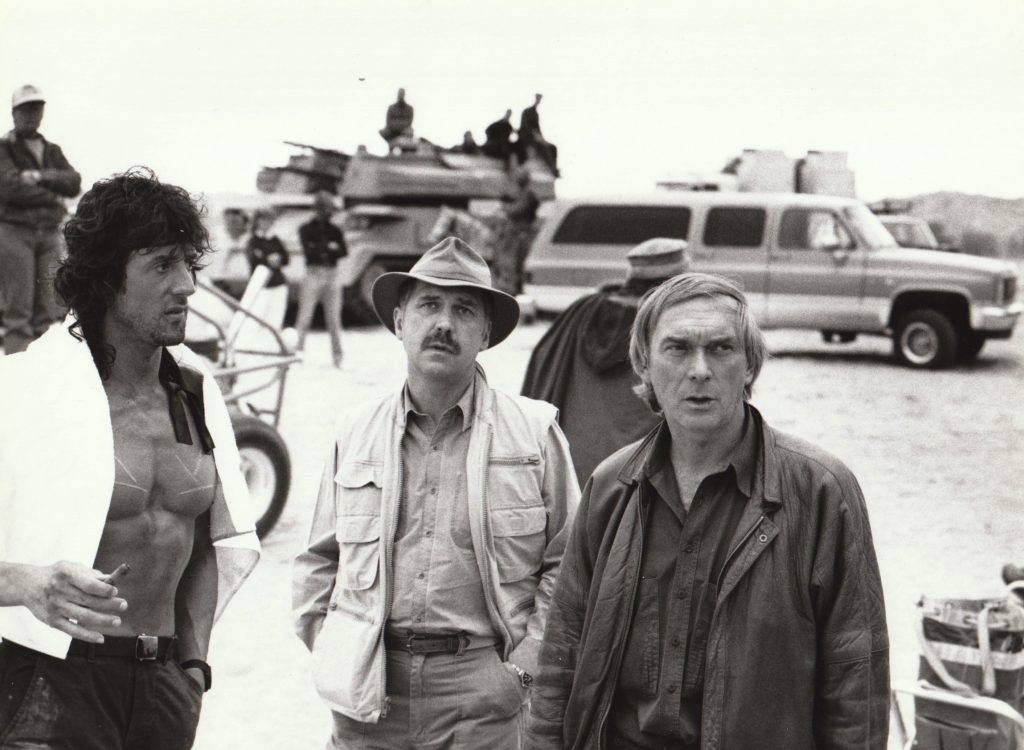

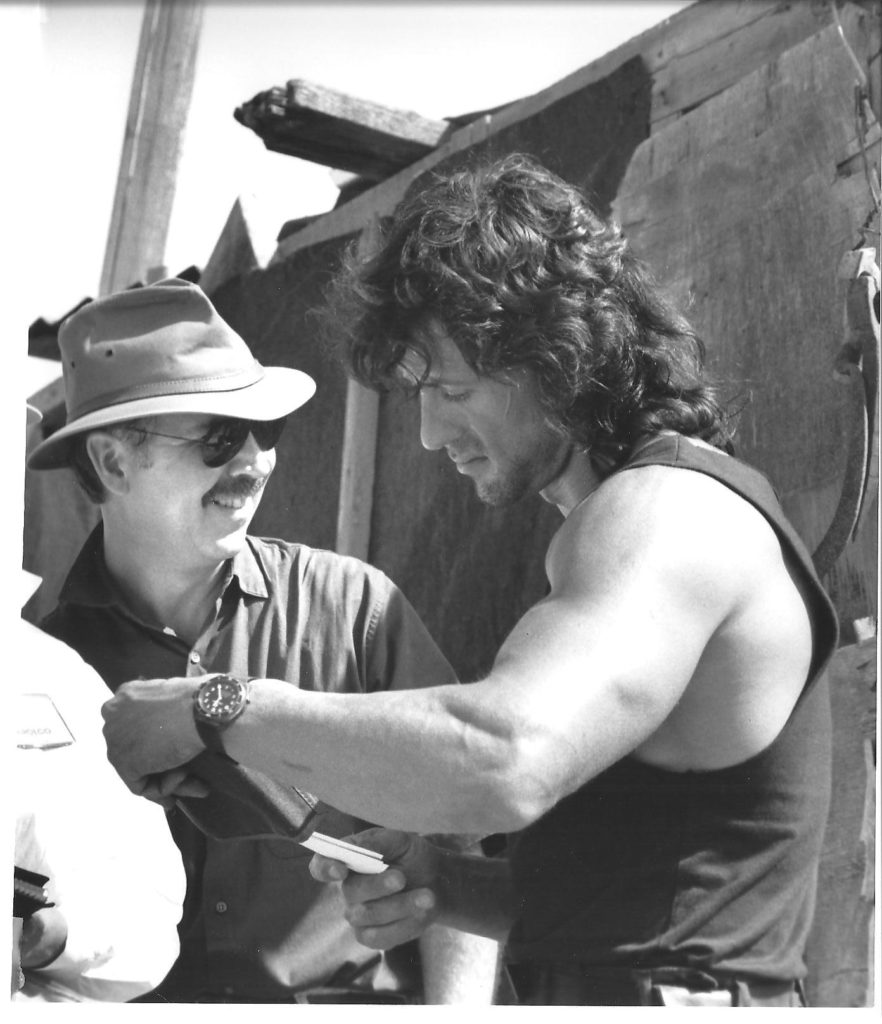

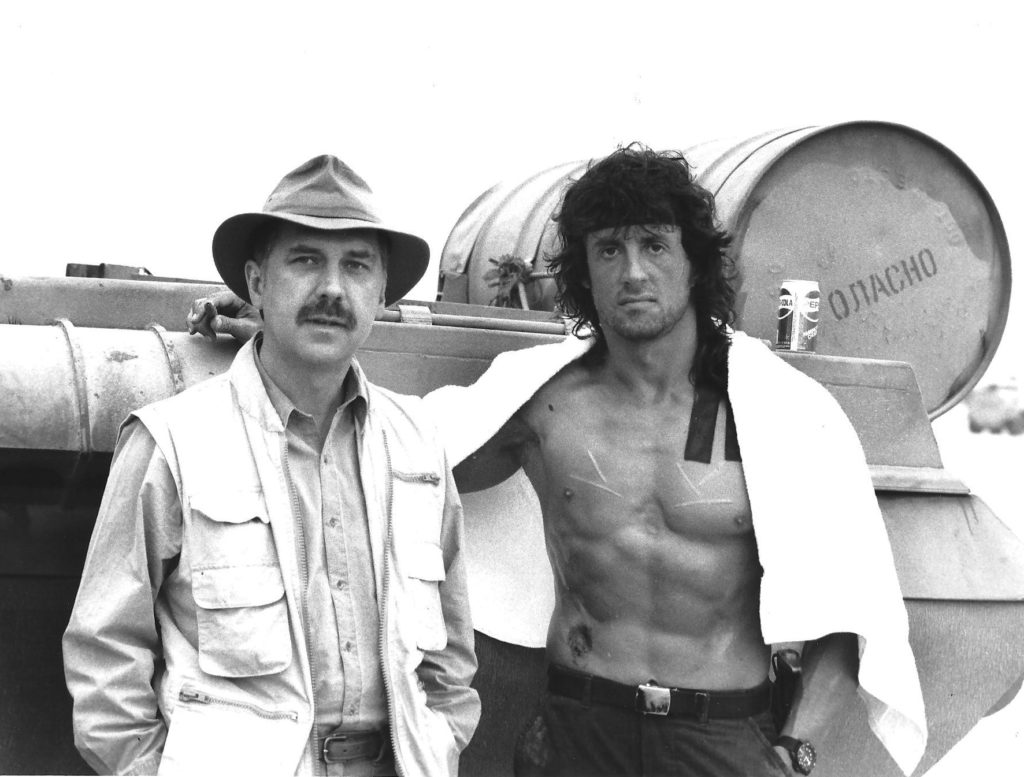

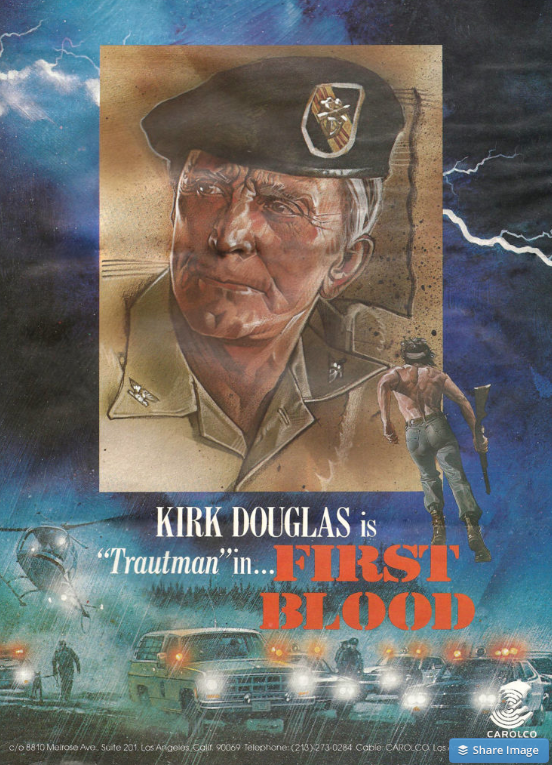

The opposite. I think the movie is excellent. Movies and books are different. Changes are inevitable. The film switches the locale from Kentucky to the Pacific Northwest. It removes the importance of Teasle’s war experience in Korea and the medals he received there. It makes Rambo a victim rather than somebody who’s pissed off about what happened to him in Vietnam. Finally it changes the ending. But for all that, I love the movie. Ted Kotcheff’s direction, Jerry Goldsmith’s music, Andrew Laszlo’s photography, Sylvester Stallone’s acting, Richard Crenna, on and on. It’s a terrific movie that seems more realistic with each year because its action scenes don’t use computer effects. The realism of the stunts is amazing.

You mentioned Stallone's acting. It’s all in the eyes and the body language. Richard Crenna had a long career. He appeared with countless film actors. He told me that, in all his years, he worked with only two actors who truly knew how to play to a camera, reacting rather than acting, using their eyes, skillfully handling props. Those actors were Steve McQueen and Stallone.

You mentioned Stallone's acting. It’s all in the eyes and the body language. Richard Crenna had a long career. He appeared with countless film actors. He told me that, in all his years, he worked with only two actors who truly knew how to play to a camera, reacting rather than acting, using their eyes, skillfully handling props. Those actors were Steve McQueen and Stallone.

You talk about this sort of thing in detail in your audio commentary for the DVD of First Blood

My full-length commentary is on most Blu-Ray DVDs of First Blood. It’s a detailed explanation about the differences between the novel and the film, along with a lot of fun details such as that the rat cave in the film was actually a much more horrifying bat cave in the novel. In the movie, the rats that Sly struggles with in the cave were actually white lab rats that were dyed brown. Some DVD versions also have an excellent documentary, “Drawing First Blood,” that analyzes how the book became a movie. I’m in the documentary, but for some reason, I look orange.

How do you feel about the other Rambo films?

I wasn’t involved with them, so I think I can speak objectively. I enjoyed Rambo (First Blood Part II). It’s a cross between a Western and a Tarzan movie. The fight in the helicopter is like a fight on a stagecoach. The arrows with the grenades on them. The wall of mud that Rambo steps out of, magically appearing. It all makes me smile. I met an instructor from Fort Bragg who said that he and his unit went to see the second movie and couldn’t stop laughing when Rambo shoots a rocket launcher through the shattered windscreen of his downed helicopter. The POWs Rambo rescued are in the back, and in real life, the back blast from the rocket would have killed them all. But the movie wasn’t meant to be realistic, and despite the errors, the Fort Bragg instructor said that he and his team loved it. Thanks to director George Cosmatos, it has wonderful energy.

What about Rambo III?

What about Rambo III?

I wrote novelizations for the second and third films, which means that I saw all the drafts of the scripts. Rambo III’s early versions featured a middle-aged Dutch female doctor, taking care of Afghan children injured or orphaned in the war with the Soviets. After Rambo rescues his mentor, Colonel Trautman, from the Soviets, the two join forces with the doctor and the children, helping them to get to safety. It was an emotional story that put soul into the action. In the final draft, all of that was gone. The story was reduced to: Trautman is captured; Rambo tries to rescue him and fails; Rambo tries to rescue him and succeeds. The repetition of rescue attempts hurts the film’s structure. The day Rambo III opened in theaters, the Soviets pulled out of Afghanistan. I guess they heard he was coming.

And the fourth Rambo film?

Some people think that the first film is called Rambo. But it’s not. It has the same title as my novel, First Blood. The fourth film is called Rambo, though, which must confuse a lot of people. Sly phoned me before making the movie and said that in retrospect he didn’t care for the second and third films because they glorified the violence. He said he wanted to go back to the tone of my novel. This time around, the character is the way I imagined—angry and burned-out. There's a scene in which Rambo forges a knife and talks to himself, basically admitting that he hates himself because all he knows is how to kill. He spends a lot of time in the rain as if trying to cleanse his soul. At the start, he gathers cobras in the jungle, and he's comfortable with them because he knows he has nothing to fear from another creature of death. The most telling line of dialogue is, “I didn’t kill for my country. I killed for myself. And for that, I don’t believe God can forgive me.”

Powerful stuff.

Yes, very daring. I just wish that the rest of the fourth film was like that. Many elements could have been better. The villains are superficial, and a lot could have been done with the connection between drug lords and the military in what the film calls Burma (it's actual name is Myanmar), dramatizing how money earned from the heroin trade motivates the regime’s ruthlessness. Instead, they’re merely depicted as psychopaths. In a baffling moment, heroin somehow gets equated with meth, which is something entirely different and has nothing to do with the poppies grown in that area of the world. Otherwise, there are a lot of nice moments, especially after the final gun battle when Rambo is back in the United States, walking along a road, wearing the same clothes that he wore at the start of First Blood. If you think about it, the character in the first film, a victim, is different from the jingoistic character in the second and third film and is different again in the fourth film, where he is close to the character in my novel. A lot of Rambos.

In a way, there's a fifth film.

Yes, a small British film called Son of Rambow. The misspelling is deliberate. It’s set in England in the 1980s. Two kids from unhappy homes decide to distract themselves by making their version of a Rambo film. They dress up as Rambo and Colonel Trautman. It’s a tender, charming story that features scenes from some of the other movies.

You mentioned writing novelizations for Rambo (First Blood Part II) and Rambo III. Some people might not be familiar with the word.

You mentioned writing novelizations for Rambo (First Blood Part II) and Rambo III. Some people might not be familiar with the word.

In the 1980s, film producers began to hire writers who expanded scripts into books that helped generate publicity for the movies. It was mostly work for hire, and the authors couldn’t change the dialogue or the scenes. Basically all the novelizers were allowed to do was add description and explore what the characters were thinking. When the second Rambo film was in production, the producers asked if I’d do a novelization. My instinct was to say “no” because of the limitations imposed on the writer. But for publicity purposes, the producers really, really wanted a novelization, and my contract stipulated that I was the only person who could write books about Rambo, so they couldn’t go to anyone else. They finally agreed to give me the freedom that a novelizer almost never has.

What happened?

Well, the final draft script they sent me was about 85 pages long and was filled with lines like “Rambo jumps up and shoots this guy. Rambo jumps up and shoots the other guy.” Not much to work with. So I asked if there were other scripts, and I was told, “Yes, the one that James Cameron wrote, but we only used bits of it.”

You mean James Cameron of Terminator 2, Titanic, and Avatar?

Yes, but he wasn’t that James Cameron yet. I asked to see the script and struck gold. In the end, my novelization was one-third original material from me, one third adaptation of James Cameron, and one third the final script. Those many differences between the film and the novelization had never been allowed before—or since. Most of the Cameron material involves the book’s opening, where Colonel Trautman visits Rambo in a locked cell in the basement of an insane asylum. I can imagine what the producers thought when they opened Cameron’s script to that. The scene probably wouldn’t have worked in the movie, but I was happy to include it. The book spent 6 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, another first for a novelization.

What about the novelization for Rambo III?

Well, that was a difficult time for me. My son, Matthew, had been diagnosed with a rare bone cancer, Ewing’s sarcoma. He had huge tumors growing out of his ribs and was in the hospital a lot, getting chemotherapy. Meanwhile I agreed to novelize the third Rambo film, partly to take my mind off what was happening to my son. The first script I received featured the middle-aged Dutch female doctor and the wounded children that I mentioned earlier. Rambo’s journey to Afghanistan was epical, including a huge dust storm. At one point, horsemen had ropes around each of Rambo’s arms and were pulling him apart.

Sounds wonderful.

I was very excited. But then a second script arrived, and the doctor and the kids weren’t as important. Then a third script arrived, and  the dust storm was gone. In the fourth script, the doctor and the kids were gone. With each successive draft, the story got simpler and simpler until it was merely a failed rescue attempt and a successful rescue attempt. Between visits to my son in the hospital, I finally phoned the producers (Andrew Vajna and Mario Kassar—I really liked them) and said, “I can’t write a book this way. Pick a script for me to expand.” But they told me there’d be more revisions, so we agreed that I’d use the script that featured the doctor and the kids. Once again, in violation of the rules of novelizations, at least half the book has material that isn’t in the movie.

the dust storm was gone. In the fourth script, the doctor and the kids were gone. With each successive draft, the story got simpler and simpler until it was merely a failed rescue attempt and a successful rescue attempt. Between visits to my son in the hospital, I finally phoned the producers (Andrew Vajna and Mario Kassar—I really liked them) and said, “I can’t write a book this way. Pick a script for me to expand.” But they told me there’d be more revisions, so we agreed that I’d use the script that featured the doctor and the kids. Once again, in violation of the rules of novelizations, at least half the book has material that isn’t in the movie.

Your novel First Blood ends differently than the film. How did you justify being able to continue writing about the character?

I should warn people that what I’m going to say contains a major spoiler. Skip ahead two questions if you haven't read my novel and don’t want to be surprised. Now’s your chance. Okay, at the end of my novel, Colonel Trautman kills Rambo with a shotgun. It’s an allegory. Trautman’s first name is Sam. He’s Uncle Sam. He’s the system that created Rambo, and that system destroys him. A version of that ending was filmed (Rambo commits suicide), but test audiences nearly rioted after cheering for Rambo and then seeing him die. So the producers went back to Hope, British Columbia, the location for the film, and shot a new ending in which Rambo lives. They had no intention of making sequels. They just wanted to have a movie that audiences liked. Then the film turned out to be so successful that they realized how lucky they were to be able to make sequels.

But you had a problem.

Again, just to alert people, this paragraph contains a spoiler also. Yes, my problem was that I killed Rambo, and now in the novelizations he would be alive. The logic really bothered me. One day, I crossed paths with my writer friend, Max Allan Collins, (among other things, he wrote the wonderful graphic novel, The Road to Perdition), who said that the problem was easily solved. “Just add an author’s note,” he told me, “in which you say something like, ‘In my novel First Blood, Rambo died. In the films, he lives.’ ” So that’s what I did. Gauntlet Press released collector's edition of both the novelizations. with plenty of extras that explain the background of how the novelizations came to be written. One of the extras is a definitive 1985 L.A Times article by Pat H. Broeske, "The Curious Evolution of John Rambo." Another extra is a 1988 Variety article, "Rambo III: Budget Run Amok--How Rambo III Became the Most Expensive U.S. Movie Ever Made."

There's an amusing story about the way you describe the knives in the films.

The knives for the first two movies were designed by Jimmy Lile, the famed Arkansas knifemaker. Sly collects knives and knew Jimmy and asked him to design the first two knives. When I was researching the knives to write about them in the novelizations, I talked to Jimmy several times on the phone. He was fascinating. Then unfortunately he died, and another master knifemaker, Hall of Famer Gil Hibben took over. I eventually got to know Gil very well. Anyway, in a foreword to the second novelization, I praised the Rambo knives as works of art. Pauline Kael, the film critic, somehow got her hands on the novelization and included it in her review, saying that she could hardly wait for her set to arrive.

What happened to your son?

He had surgery that removed his right ribcage, but the surgeons couldn’t get to all of the cancer, so my son then had a bone marrow transplant. He eventually died from septic shock because his immune system was compromised. One of my granddaughters, Natalie, died from the same rare bone cancer. Only a few hundred people get the disease each year in the United States. When Matt was sick, Sly phoned him late one afternoon. As it happened, Matt had two friends with him, and (you wouldn‘t believe this in a novel), they happened to be watching the videotape of First Blood. So Matt’s two friends watched him talk to Sly. I couldn’t help smiling when Matt (a show business junkie like me) asked about the box office receipts on Sly’s latest film. They talked for about twenty minutes. It was a nice thing for Sly to do. In my career, I’ve had tremendous luck. My private life, my son and my granddaughter dying so young, that’s another matter.

As David indicated, much of the material in this discussion is the short answer. For an in-depth description of why he wrote First Blood, read his essay Rambo and Me: The Story Behind the Story, which is described on the E-WORKS page of this website and is included in the Gauntlet Press collector's edition of Rambo (First Blood Part II).

David’s introduction to his novel First Blood (included in the Gauntlet Press collector's edition of First Blood and in paperback editions of the novel) is also informative as is his full-length audio commentary on many Blu-Ray DVDs of the film.

If you have questions about Rambo that David didn’t answer in any of these places, you can contact him through this website.

David Morrell’s debut novel, First Blood, inspired the most-famous knife in modern history, created one of the world’s most recognizable characters, has never been out of print since 1972, and has been translated into thirty languages. This fascinating Blade magazine article describes the history of the knives.

(Warning: There are spoilers in this essay. If you haven’t read First Blood but intend to and you don’t want to be surprised by the book’s harrowing climax, read Steve Berry’s essay afterward.)

In the summer of 1968, America was erupting. The Vietnam War was literally tearing the nation apart, riots and demonstrations so polarizing the country that one generation seemed utterly confounded by the other. Recently arrived in the United States on a student visa was a twenty-five year old Canadian named David Morrell. He was married, with an infant daughter, preparing for a career as a teacher, fascinated by the United States, eager to learn about something he knew nothing about: the Vietnam War.

What he discovered deeply disturbed him. But something Socrates once said came to mind. No one commits wrong intentionally. For Morrell, that truism about how we rationalize everything we do became worth exploring, so he decided to write a novel that would allegorize the Vietnam War. Not to make a point. Or take sides. That could have been a problem since the terms of his visa specifically stated, on threat of deportation, that he should refrain from expressing political opinions. Instead, Morrell decided to tactfully objectify America’s bitter philosophical and cultural divisions, transposing the brutality of Vietnam—and the radical conflicts that the war generated at home—to a rural Kentucky town, creating a miniature version of the Vietnam War on American soil.

Instead of shotgunning the narrative with many points of view, he focused on only two. Rambo, the Vietnam veteran, Green Beret, former POW, and Medal of Honor recipient. A man haunted by the war, repulsed by the violence he found in himself, embittered by the hostility he sometimes faced from those he fought to protect. In rebellion, he allowed his hair and beard to grow, shunned all possessions, and wandered the back roads of America, looking like a hippie. Searching, he represented those disaffected by the war.

Wilfred Teasle represented the Establishment. A Korean War hero, recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross, Eisenhower Republican, chief of police in Madison, Kentucky. As troubled as Rambo, he’s old enough to be Rambo’s father, haunted by a different set of war memories, but equally as controlled by them. By alternating back and forth between each man’s anger, Morrell allowed the reader to identify with each man’s motivations. As with Socrates—no one commits wrong intentionally—these two likewise draw from deep, well-meant convictions, making one mistake after another, their rationalized fury eventually guaranteeing a mutual destruction.

Morrell was careful not to favor one character over the other. He wanted the reader to understand both sides and become dismayed as the two protagonists proved incapable of doing the same. At one point, Teasle sends for the Special Forces officer who trained Rambo—Colonel Sam Trautman, whose first name Morrell meant to echo that of Uncle Sam. In the end, after Rambo kills Teasle, Trautman kills Rambo, thus completing the allegory inasmuch as the representative of the system that created Rambo is the person who destroys him and turns out to be the only winner.

The palpable vividness of the prose in First Blood is matched by the book’s unrelenting pace. Until its publication in 1972, few thrillers dramatized so much intense, continuous action. From the moment Rambo breaks out of jail totally naked and hijacks a motorcycle, escaping into the nearby mountains to fight a private war, the novel set a new standard for speed. It also established a fresh approach to writing action, based on the research Morrell did for his Master’s thesis on Hemingway’s style. Hemingway didn’t use clichéd expressions such as “A shot rang out,” and Morrell was determined not to write that way, either.

Often referred to as “the father of the modern action novel,” First Blood has sold millions of copies around the world and remains in print to this day. Inevitably, Hollywood discovered the tale and created four films, not to mention a Saturday morning cartoon series. The fact that the second and third films (and the cartoon) are false to Morrell’s initial concept is irrelevant. The films exist in worlds of their own and, collectively, manufactured a pop-cultural icon—Rambo—one that aided an emasculated America, in the 1980s, to feel good about itself again: Ronald Reagan’s so-called “new morning.”

Reagan himself elevated Rambo as his standard-bearer in numerous press conferences, once remarking that, having watched a Rambo film, he knew what to do the next time there was a terrorist crisis. Morrell himself experienced the phenomena when, one day in 1986, he was on a publicity tour in England and picked up the London Times to find a disturbing headline: US Rambo Jets Bomb Libya.

Not exactly what he had in mind when he first created that all-too-real conflict between Rambo and Teasle. A novel that questioned war and its devastating aftermath, a story that brought to life lingering cultural wounds left by the Vietnam debacle, became a shorthand political metaphor—a rallying cry for even more violence. Morrell himself commented on the irony that a 1970s novel about the political polarization of America (for or against the Vietnam War) became the basis for films, in the 1980s, that resulted in a similar polarization (for or against Ronald Reagan).

Eventually the Oxford English Dictionary cited First Blood as the source for the creation of a new word. Rambo. Complicated, troubled, haunted, too often misunderstood. Precisely like First Blood itself.

*

Steve Berry is one of the world’s most popular thriller novelists. He began writing in 1990, and although he is an attorney and his undergraduate degree is in political science, Steve’s interest in travel and history led him to write international suspense thrillers. His many New York Times bestsellers include The Third Secret, The Templar Legacy, The Venetian Betrayal, The Charlemagne Pursuit and The Jefferson Key. His latest is The Columbus Affair. His books have been translated into 40 languages and sold in 51 countries. He is a former co-president of International Thriller Writers. You can learn more about him at www.steveberry.org.

(Steve Berry’s essay about First Blood originally appeared in Thrillers: 100 Must-Reads, a non-fiction collection nominated for Edgar, Anthony, and Macavity awards. One hundred modern thriller authors wrote essays about their favorite classic thrillers.)